In TTRPGs, should you have rules for roleplaying?

Would a game be better if it had as much crunch for the storytelling side as most games give to combat?

Is there some secret combination, some formula that you can follow that will guarantee high drama and all the feels at your table?

Well yeah, kind of. But as with so many things, the rules are more like… guidelines.

Today I’ll share what I’ve discovered with a little help from a friend – how Daggerheart and Brindlewood Bay incorporate roleplaying rules, but also how you can take that little golden nugget, that little shining part of this approach and port it into any system.

Though first, why would you want any rules at all?

I want guidance at the things I’m bad at, and I’m bad at writing stories and creative writing in general. I’ve not done it seriously since I was about in high school English classes.

I like the outdoors. It’s my happy place, and I find the rules for exploration for the wilderness in TTRPGs to be frustrating, because I already know quite a lot about it, and I’d much rather substitute for my own inventions.

Different people with different expertise will find various parts of the game frustrating. A great example is Ben, champion sword fighter, who really does not like the rules for combat in DnD.

I think one of the key things is people really, really don’t understand how light swords are and how fast swords are.

Swords are designed to be light, fast, and razor sharp.

That’s their context, you know?

So for instance, all the kind of the action economy that you might find in Dungeons and Dragons is way too slow for real swordsmanship, way too slow.

Or something like a Highland broadsword.

You’re thinking about like multiple actions much, much faster.

You could have like classically seen an Highland broadsword, you’d be throwing parry reposte, parry reposte, you’d be like a level fighter in real life, you know?

That’s how many things you’d be doing for action economy.

I am not a game developer or designer, but if I had to invent a system for Ben, letting him narrate in all sorts of detail, the different maneuvers that his character makes, with maybe only a single dice roll needed to determine the outcome of a fight, I’d give advantages for sharing a good description of what thrusts and parries and other sword things that his character then chooses to do.

When I’m outside, I’m in my happy place. I’ve got my compass, I’ve got my whistle, and I know how to use them. Champion Boy Scout, Orienteer, all of those things.

But what that means is when I see mechanics for “here is how you should adventure, here’s how your character should move through wilderness”, I don’t like it.

I find it strange and unnatural, which often takes me out of that narrative flow state and I start poking holes in mechanics, which is just not fun for me. My preference is for games that leave the exploring up to the imagination.

But if you’re not an outdoorsy person, you won’t feel supported in that.

This is pretty much what happens in the narrative side of so many TTRPGs. It gets simplified down to “just talk and we’ll then decide whether it works or not” The social side of TTRPGs is nowhere near a match for the detail and crunchiness of simulating combat in most games.

So the question then becomes, well, what would a system look like which was as crunchy in narrative as DnD is in combat?

After chatting with a few folks on my Discord server, which you should totally join by the way, the consensus between us was that there are mechanics to role-playing, but they’re not something you should use dice for.

The mechanics of making interesting and compelling roleplaying scenes are actually the mechanics of improvisation and storytelling.

As a player, taking the time to really think about your character, think about what they would do in this moment and if this is true, what else is true? You can build a lot.

It’s at this point that Peter from Tales from Elsewhere jumped in and really helped me distill this thinking down into something dead simple.

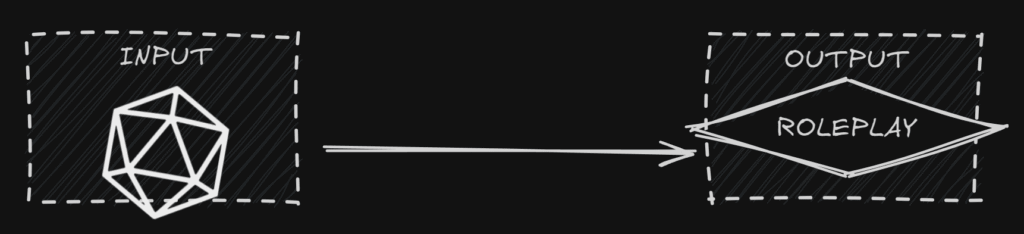

To paraphrase him, if we break this down into a schematic where we’ve got an input and an output, we know we want cool roleplay to happen at the end.

So you might think at first, okay, let’s put roleplay as an input and then let’s roll some dice on the right as an output.

Let’s roll some dice in and get roleplay out. That sounds good.

But here’s the thing, if you roll a ton of dice and say, okay, I’ve got persuasiveness of three and I’ve got ten on my charm and wit, that doesn’t give you roleplay out.

That gives you a framework that you could roleplay around, but it doesn’t make a compelling moment at the table.

Using dice, you’ve achieved specificity, but it’s got no charm.

It’s got no soul to it.

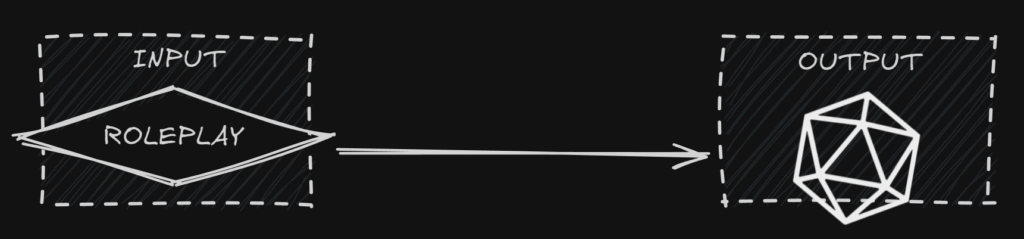

Instead, Peter suggested that we flip this around.

If we take roleplaying as an input and the output is some mechanical advantage, something in-game, something tangible, then we get something interesting.

We both recently played in a game of Brindlewood Bay, which was run by Salty Nick.

In that game, with the best of premises, you are little old ladies solving crimes.

Something that really sets that game apart and encourages so much roleplay is that there are tangible mechanical rewards for roleplaying and that fits this schematic, this way of thinking, perfectly.

Another game which gives mechanical reward for roleplay is Daggerheart. Part of the character creation is coming up with experiences. Little one-line descriptions or quotes of things from your past.

For example, during my Daggerheart actual play, which you should totally watch too as it’s really good, one of the characters, Verdi, had “you can’t fight the wind” as one of her experiences. And whenever that was applicable, whenever it came up, you got a plus two bonus on a roll.

What this means is that players are always looking for opportunities to tie in situations to their past, to their backstory, and we found that we had bits of character building happening all the time.

Likewise, one of the downtime activities is you can describe how you prepare for the coming ordeal, and that gives you some more Hope points.

On some of the very shiny ability cards as well, you have things like Lead by Example:

“When you deal damage to an adversary, you can mark a stress and describe how you encourage your allies.”

This isn’t much, it isn’t a big deal. It’s the kind of thing lots of groups already do as part of their games.

But to see it codified, to see it written down, to see it as an expectation of the game that it wants you to do this is really interesting.

But I have noticed that for some of the abilities on the cards, they don’t necessarily give you an open-ended question that helps you develop the character.

It’s more just you need to describe what you do in this moment, which could feel repetitive, especially if you’re playing for a long campaign.

One of the criticisms that’s pointed at Daggerheart is that it’s DnD for theatre kids. But I disagree with that completely.

I think what Daggerheart has done is they have created a game for people just like me who maybe wish they had the opportunity to be theatre kids, to find those creative outlets from a young age.

The fact I’m only just discovering some of my creative voice now is thanks in part to role playing games, which gives the opportunity for people with no storytelling background to find amazing adventures.

And games which have the support for the narrative side really do stand out from the crowd of role playing games.

Some good news though, you don’t need to be playing Daggerheart and you don’t need to be a little lady solving crimes in order to have this kind of experience at your table.

The idea of encouraging role play and giving some narrative reward is present in lots of systems. DnD has it in the inspiration mechanic.

But if you’re looking to add more structure, if you’re looking to make this a systemic part of the way that you play, there’s a few things you can do.

Number zero on this list is your regular reminder to talk to your players, everything’s easier when you do.

And if you know you’re on the same page and you know you want this kind of experience, it’s much easier to make it happen around your table.

Number one is actually to start at the end.

What’s a good reward? What’s a good mechanical bonus for this kind of behaviour?

In DnD that could be something as simple as advantage on a roll. There’s no need for the advantage to be game breaking. There’s no need to have people feeling forced to do this.

It’s about a small bonus to encourage this narrative side.

Number two is to expand on the Matt Mercerism of “how do you want to do this?” as well as players describing the how of their action.

Have some questions on hand. Why are you doing this? How do you feel in this moment? What does this remind you of in your past? What are you afraid will happen if this doesn’t work?

As GM, I love peppering the conversation with these little questions. It slows down the game a little, but for me it leads to a much deeper experience and a much more interesting time.

Lastly is encouraging your players to do this to each other. Letting them ask questions of each other’s characters is a great way of almost being a collaborative game master with them.

We’re all working together to know these characters better so that when the big events of the adventure happen they have a much stronger answer to what would my character do?